Optimism, Pessimism & the Loch Ness Monster

Why unintended consequences are bigger than good or bad intentions.

I am sometimes called a pessimist by people who read my essays and novels, and on occasion, I’m hired to take part into public debates with people who want to look more positive and optimistic by having me as their dark, cynical nemesis. I’m the pessimist-for-hire who, by contrast, shows them in a better light. I have stopped taking invitations for such things, because although it can be an enjoyable role to play, I am not really a pessimist.

What am I then? And what might the legions of us non and anti-optimists really be?

Looking back, I’ve certainly been influenced and inspired by one of the great pessimist philosophers - Arthur Schopenhauer, with his belief that pre-figured Darwin, that the world is ruled by chaotic and pointless striving which leads to suffering; the blind force within all living things that he named “The Will” - which would later morph into Nietzsche’s Will to Power. Moving beyond such atheisms, even the religions I have found any affinity with, Buddhism and Christianity, are both deeply pessimistic in their belief in the core experience of existence as being, again, one of aimless suffering. It’s hard not to disagree with these two faiths that there is a deep flaw within human nature, that as Immanuel Kant said, “Out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing was ever made.” Like many of my generation, I have also spent many years grappling with nihilism, and pessimism is often seen as the gateway to nihilism with its belief that ‘nothing has any inherent value.’

However, the problem with separating people out into pessimists and optimists is that none of this deals with the real business of this fleshy existence, which is that of outcomes, or consequences.

Real-life outcomes expose the limits of both optimism and pessimism, both of which appear like magical thinking when measured up against actual outcomes. But what has this to do with the Loch Ness Monster you ask. We’ll get to that soon.

The optimist believes that - by some magic or collective universal force - possessing good intentions will lead necessarily to the desired positive outcomes. They believe that the sheer force of positivity in the world will lead to things turning out the way that they want them to. As the corporate screensaver slogan says, “positive thoughts lead to positive outcomes.”

It’s interesting how much corporate culture and techno-capitalism depend upon feeding us the constant mindset of optimism, the way they endlessly remind us to focus on our own future happiness as reward in itself. Be hedonistic, they say, seek pleasure, pleasure is real and you’re worth it. This corporate optimism always reassures us that success and happiness will be ours if only we believe in ourselves enough. High end speculative capital also operates on ‘Market optimism’, and the speculative economy is roughly 4.3 times larger than the “real economy” of GDP and goods. The speculative economy is currently estimated to be $379 trillion, that’s a lot of optimism.

A pessimist, in contrast, believes that everything is fated to fail. Doomed. Nothing you do will amount to anything. Everything is fake. Everything is falling apart. The planet is going to be eaten by the sun in 2 billion years anyway, so its all pointless, so why get out of bed?

Both of these opposites suffer from what I would call the intentions fallacy, which is a version of the older ‘righteousness fallacy’ – the idea that everything that righteous people say and do is good and will turn out positive. And in its inversion, everything that doomed people will do will always turn out negative.

The intentions fallacy

With the intentions fallacy, we have the idea that when we set out to do something specific, with good intentions, everything will turn out the way we want it to provided we plan well and have good intentions, and conversely people with bad intentions will commit only bad acts. This is what an optimist believes. Conversely, a pessimist believes that people who state good intentions, really have bad intentions and therefor things will end badly.

What both optimism and pessimism completely omit - and the history of the world shows this clearly - is that everything we do is affected by unintended consequences. The Scottish philosopher Adam Smith (1723-90) came up with the ‘law of unintended consequences’ and said that the larger an enterprise we undertake, say the building of a damn or a road or a new architectural structure - the greater the unintended consequences down the line will be. The bigger your plan, the more unpredictable the outcomes.

Smith warned against the righteous fallacy, and the planning fallacy - the belief that simply because we have planned something - to “change society for the better” - that everything will go according to plan, including a host of consequences that lie, unseen and unpredicted, beyond the scope of the plan.

There are many examples in the 20th century of vast optimistic plans of human engineering that had immense unintended consequences. For example, you have the manufacture of dams for the purposes of hydroelectric power and irrigation, which nonetheless cause drought and starvation hundreds of miles away and even in different countries. Ethiopia and Egypt are currently at war over the Nile dam. A new dam in Turkey may be about to trigger a war with Syria and Iraq.

There is one huge example of unintended consequences which which should be a warning to us all, particularly those of us who see ourselves as optimistic social planners. It comes from ‘The Great Leap Forward’ of Mao Zedong in Communist China.

Mass unintended death

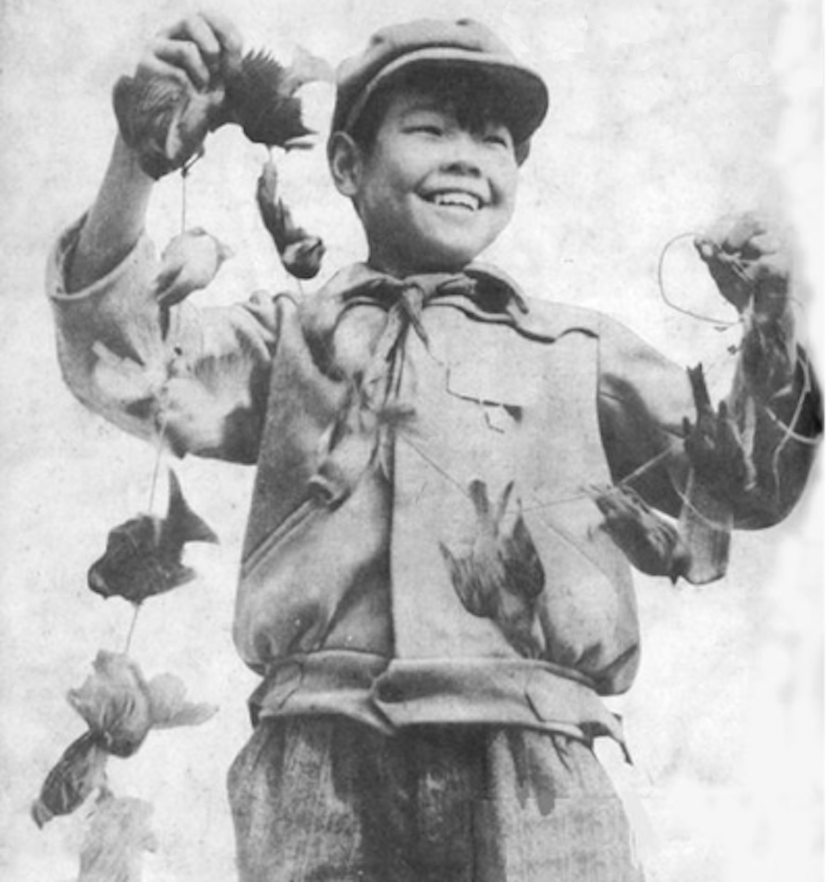

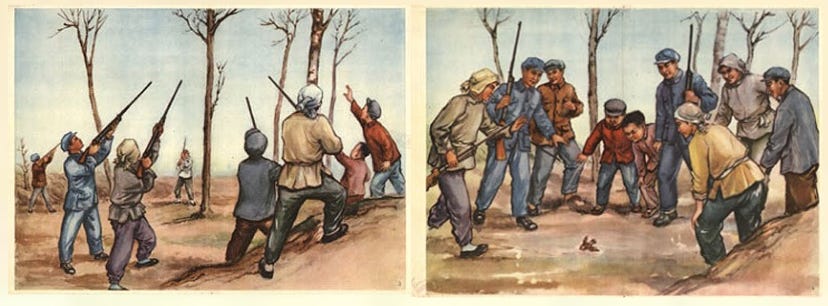

From 1958 to 1962 the Communist Central Committee in China created the most optimistic piece of social engineering that has ever been attempted in that country, it was planned to unify the entire populous with a noble common goal, it was called the Four Pests Campaign. The great project to mobilise the masses was the eradication of pests from China; pests that were seen as contributing to sickness and starvation. The four pests were designated by the central committee as rats, flies, mosquitoes and sparrows. Sparrows stood accused of stealing grain from the fields and granaries of the workers collective farms. Sparrows were a metaphor for the selfish ‘thieving Capitalists’ that had to be eradicated. The extermination of sparrows was known as the ‘Smash the Sparrows’ campaign and there were anti-sparrow songs composed, and films made that depicted young children with catapults killing sparrows and children carrying buckets and wheelbarrow loads of dead sparrows and dumping them into large pits. Although this sounds horrific to us now, at the time this was seen as an optimistic project that would unify the whole nation and save millions of tons of grain.

The imagery around the Smash the Sparrows campaign always showed brightly-clad, happy, smiling children with catapults, spades and buckets working together for the common good of all.

The unintended consequence of the murdering of 1 billion Sparrows by the population of China was a massive ecological imbalance. In their optimistic calculations the spreadsheets of the social planners had not foreseen the consequences of killing so many birds, had not calculated what the birds themselves ate.

And so, in the years after the smash the sparrow campaign the crops in China were eaten by millions of locusts and other insects that had been traditionally kept down by the sparrows. The unintended consequence of this vast plan of optimistic social engineering was the Great Chinese Famine of 1969, during which 20-43 million Chinese died. In certain provinces starving people had to eat mud and bark of the trees to survive and in one province there were reports of cannibalism.

None of this had been planned, the unintended consequences were much greater and much worse than anything in the master plan itself. An optimist would never have seen this, even a pessimist could not have estimated the severity of the unintended consequences. It would have taken a cautious sceptic to have spotted the danger in advance.

A sceptic might have looked carefully at the spreadsheet plans and tried to work out what factors were excluded and what the unintended consequences might therefore be. A sceptic could’ve said let’s implement this in one state only on a trial basis, rather than imposing it on the entire nation of China with its population of 664 million. Communist China with its future-optimism and planning-optimism, became the greatest perpetrator of man-made human deaths in the 20th century

And here we see another of the great defects of optimism which is that the optimistic social planners who see, to their horror, that they have created a disaster cannot actually face the reality of the outcome, cannot take responsibility for the unintended consequences, so instead they put their energies towards concealing the evidence of the disaster. This is why, to this day, the estimates of the number of people who starved during the great Chinese famine vary so greatly; so many records were destroyed or falsified by the state. And we must remember that communism itself is the quintessentially optimistic belief system. It believes that human beings can be improved upon and scientifically re-engineered for maximum peace, happiness and health. Communist doctrine, which grew out of 19th century utilitarianism and scientific optimism, believes that human beings will inevitably progress towards a perfectly planned society in which total equality will be achieved and all human needs measured and served. Communist do not believe that man is made of bent wood that can never be straight, they believe that man can be shaped by the forces of positivity progress and optimism. The communist and indeed today’s progressive belief about human nature is that it is a blank slate, on which the better future can be drawn.

But they ‘Meant Well’

One of the great problems with communism is that, still to this day, we have let the communists, the far left and the democratic left who support them, evade so much blame and accountability for their ‘unintentional crimes’ in the 20th century, simply because ‘they had good intentions’. Their intentions were better than the other totalitarians, we say, Hitler is worse than Stalin because Hitler clearly had genocidal, intentions, where as Stalin ultimately ‘meant well’ because he was a good progress-believing Communist who believed in a one-world centrally-planned government that would solve all problems for all mankind, forever. The fact that the genocide caused by the communists is seven times greater than the deaths caused by the Nazis does not factor into this equation because we ourselves live in a culture dominated by the ideology of optimism and one that turns a blind eye to real outcomes and unintended consequences unleashed by optimistic people.

Any truly consequentialist culture would assess a society on its actual outcomes and would see that the communists in the 20th century across the many countries that they controlled killed over 100,000,000 people and would come to the calculation and conclusion that the most murderous belief system in history was communism.

However, because we live under the intentions fallacy, the optimistic fallacy and the planning fallacy, we let the communists off with their mass genocides because, we say ‘they didn’t mean to kill so many people, their ideal is still a good one at heart.’ And then we foolishly go on to say that communism still being a good idea, it might be time to try to put it into action once again and to do it properly this time, with better planning, with better leaders, with renewed hope and positivity.

This is the tyranny of optimism. Everywhere optimistic ideology takes hold there are secret gulags and hidden graves filled with all the people who didn’t fit into the spread-sheet idealist plan. When someone says ‘optimism’ there is a sweet stench of denial and death.

A more up-to-date version of unintended consequences, again occurring with the institution of a very large project of social engineering is what happened with Bill and Melinda Gates ‘Spread the Net’ project.

This was a recent project in Africa intended to stamp out Malaria. The foundation gave 500,000 free mosquito nets to rural populations within Rwanda, Liberia, Uganda and Guinea. These nets stopped mosquitoes, as per the grand plan, but they were also extremely good for catching fish because no fish could escape from the very fine mesh. The result was the chronic overfishing of these areas and the polluting of the water with the insecticide that was within the fabric of the mosquito nets.

Another little-known unintended consequence is that the financial aid that was given through “Live Aid” (1985) ended up flooding the famine ridden country of Ethiopia with free grain, forcing hundreds of thousands of other farmers into bankruptcy and extending the duration and severity of the famine.

It is not simply that people with good intentions and optimistic world views make mistakes, it is that people with optimistic world views tend to impose one single big solution on everyone and are oblivious to how the scale of their plans is itself ushering in problems. Then when these unforeseen tragedies unfold these optimists spend their time hiding the evidence of their great error. They are only human after all, and guilt is one of the things we cannot stand to experience, especially if we have been conditioned to believe it is best to think positive things about oneself all the time.

Another unintended consequence which is very recent is the creation of a pandemic by scientists working in a laboratory in Wuhan, China. The intentions were apparently good; gain-of-function viral research is supposed to discover future deadly viruses and help us develop vaccines for them in advance, but the unintended consequence was a laboratory leak of a new lab-made coronavirus. And again, the scientific optimists who set out to do this have spent a great deal of energy trying to hide all evidence, to shut down all debate, and to demonise anyone who tries to get to the truth. The estimates are of 20 million deaths worldwide, while the total cost of the pandemic is estimated, by the NIH, at more than $16 trillion. On top of that, rather than banning gain-of-function viral research in Bio Tech labs worldwide, different nations are now building more BSL-4 labs and the gain-of-function industry has grown.

Unintended Good & The Happy Plesiosaur

One of the great ironies of unintended consequences is that they also work in the opposite direction, for the better - so you can have accidentally good outcomes that were not foreseen. For example, many drugs today were discovered through a process of unintended outcomes - Viagra was originally developed as a drug to treat heart related chest pain. It has since been discovered that the effective male-erectile medication is also effective in treating Alzheimer’s. On another front, antidepressants were originally intended to treat Tuberculosis. The drugs themselves did not do anything for TB but patients experienced a lifting of their mood. The increase in serotonin and positive feeling was actually just a side-effect of the drug. 37 million people now take SSRIs. 7.7 people out of a hundred take anti-depressants in Denmark.

There is another rather bizarre real life story of unintended consequences from closer to home. It goes like this and starts with a question - what does King Kong have to do with the Scottish Tourist Industry?

Okay, well we have to go back to 1932 and a Hollywood studio called RKO. RKO had created a huge jungle film set and lots of models for what was going to be the world’s first animated dinosaur movie (called Creation). The financing fell through and so they themselves with a whole bunch of useless dinosaur models and a huge empty jungle set, so an ingenious producer came up with another way to utilise them. He pitched a movie called King Kong which would involve nothing more than making one more model - a large ape. The idea got green-lit and this is the only reason why King Kong fights dinosaurs in the 1933 movie. There is no other reason in narrative terms why a very large ape is fighting dinosaurs that pre-existed it by billions of years.

This is a happy tale of the unintended consequences of one film being shelved and some other people making do with what was there. But the unintended good news doesn’t stop there, one of the dinosaurs in the King Kong movie was something like a long- necked, hump-backed, flesh-eating Plesiosaur - ridiculous because plesiosaurs are herbivores.

Anyway, in the movie King Kong, a man is attacked by this very long necked lake dwelling dinosaur, and the movie became a success and circulated round the world in 1933. Lo and behold, towards the end of 1933 was the first sighting of a Plesiosaur type-monster in Loch Ness and there was a piece of photographic evidence to prove it - coincidence?

A year later the famous photo of Nessie appeared, looking very much like the Plesiosaur in King Kong. Photographic analysis of the famous photograph forty years later showed that the ‘monster’ was very small, probably less than a metre long and this was ascertained by the size of the rippling waves around it which were huge in comparison to the so-called dinosaur. A deathbed confession in 1994 at the age of 93, by the stepson of one of the reporters of the first ‘evidence’ confirmed that Nessie had been a fake from the start, a hand-made model. They had constructed it because people had been talking about dinosaurs since King Kong had come out.

The unintended consequences of all of this is that the highlands of Scotland - which is a sparsely populated area which had very little reason for visits by outsiders in the 1930s - saw an immense surge in tourist traffic following the “discovery of the monster”. Nessie became a global sensation, which has lasted up until this day. Every year hundreds of busloads of tourists from around the world come hoping to snatch a picture of the improbable Plesiosaur. It is estimated that the value of the Loch Ness monster tourist business is £25 million a year, with Nessie tours, Nessie-themed merchandise, fluffy Nessie toys; there was even a serious scientific exploration to the depths of Loch Ness in the 1990s searching for the monster who had only ever existed in the movie King Kong.

Amazing really that the unintended consequences of a film studio in 1933 shelving a dinosaur film led to a completely unrelated industry worth tens of millions in an entirely different country. (And let’s just hope that there are no unintended consequences to me bursting the bubble on the Loch Ness monster myth as I would want there to be thousands of people losing their jobs as a result of my little bit of truth telling.)

So, I’m certainly not an optimist but neither am I a pessimist. I think outcomes are unpredictable and we need to learn from history and its many mistakes and take stock not just of the evil people who did terrible things intentionally but of the people with good intentions who did appalling things by accident too. And let’s not forget the people with negative intentions who did positive things by accident!

Modern society today is suffering from an excess of optimism and is guilty every day of the planning fallacy and the intentions fallacy. The American positivity movement keeps this going with its strongly loaded ideological phrases that become mantras in the workforce, and this insistence that we tell all of our workmates and friends all the time that they are ‘awesome’ that they are ‘beautiful’ ‘talented’, ‘the best’ - that our group is the ‘best ever’. This entire corporate meme culture of enforced smileyness. On the flipside - the enemies of progress are seen as the people who are negative and who question everything. This distrust and dislike of sceptics is as powerful today as it was in Communist China during the Sparrow Campaign.

The harms done to positivity kids

There is also the contradictory and damaging belief that we feed to kindergarten children as part of the positivity ideology: on the one hand we tell little kids that they are all awesome and all unique, and on the other hand we tell them they are all equal and the equality is a wonderful thing. So really you have two kinds of positivity at war with each other in the battle for what’s more optimistic and the results are very confusing for children who then grow up into adults with cognitive dissonance who believe that they are both uniquely awesome and at the same time that they have to be equal to everyone else, or the same as everyone else, because this is ‘good’.

The impact of positivity ideology on children in the last 30 years is yet another one of these experiments in social engineering that is having unintended consequences and the depression we see among Generation Z is a direct unintended result of “positive parenting” and the “positivity movement” that has become so dominant since the 1990s. Tell every child that they are amazing and that everything will turn out just great if they believe in themselves and are optimistic - and when they find out that’s not the way the world works, these kids get become disillusioned and demotivated. Deeply so. Generation Z, are in a lot of trouble and reporting the highest ever cases of mental illness.

We could do with having an honest accountancy of the unintended consequences of all of this optimism and self-help do-goodism we’ve been pumping into our culture since the technological optimism of the 19th century overthrew religious pessimism.

The surest sign of optimism as ideological project is this declaration that if we can just teach people to stop being negative then negativity will vanish, that if we can just teach people how to love and share and not be competitive with each other, then people will live happy, optimistic, sharing, caring, loving lives. Like I say, we’ve been constantly telling ourselves this since the Baby Boomers now and the evidence of the unintended consequences are all around us. Teaching kids non-competitive and non-contact sports did not lead to a decrease school bullying because of the unintended consequences of a new invention called the smart phone and the explosion of cyber bullying, that came to replace ‘contact based’ bullying. Anti-bullying campaigns have been shown to lead to school children identifying as victims, thinking they will be rewarded for declaring they are victims - and so skewing the data, which then demonstrates that school bullying has increased since the introduction of anti-bullying campaigns. Good indentions never lead to good outcomes in a straight line because humans are made of twisted wood and we can’t see the future.

It’s not pessimistic to face that. It’s just honest, and it comes from a place of concern.

So when people ask me if I’m optimistic or pessimistic about the future of the human species, I reply that the unintended consequences of either belief system are more powerful than mere intentions. Not everything is doomed and not everything is going to work out the way you want it. So ultimately, human beings might do a lot better to study unintended consequences throughout history and try to work out what the unforeseen variables are in the ambitious things we are trying to achieve.

Good for the Grey Goo Guy

What, for example are the unintended consequences of the creation of artificial intelligence and the implantation of nanotechnology within the human body? There is such a lot of technological utopianism around such enterprises and they would seem to be the next great piece of social engineering which the world is completely unprepared for.

For example, it’s a very good thing that some clever scientist (K. Eric Drexler in his 1986 book, Engines of Creation) came up with the grey goo hypothesis. Basically, the Grey goo hypothesis says that at some point in the future a nano technology that is self-replicating will be created and programmed to reproduce by feeding on existing organic material. As a result of many optimistic experiments on how well they reproduce themselves, these tiny, hungry nanobots will escape the lab and reproduce exponentially by feeding on crops, on trees, on water, on buildings, on animals and finally on humans, so due to the mathematic amplification effects of exponential growth it would take less than a month for the entire surface of the planet to be covered in, and replaced by, self-replicating nanobots or ‘grey goo’.

This is a good example of the kind of forward thinking that looks into unintended consequences and is sceptical of techno-optimism that fuels the unregulated, unchecked growth of artificial intelligence and nanotechnology. Would we call the scientist that came up with the grey goo hypothesis a pessimist, who was being unnecessarily negative ? Or should we see them as a useful sceptic, who has looked at all possible future outcomes fearlessly and with insight and imagination and has delivered a warning that could save our species from the unintended consequences of unchecked techno-positivity?

So, next time someone calls you a pessimist, ask them what they think the unintended consequences of a future built on optimism might be.

Ewan Morrison’s new novel, For Emma, explores the consequences of runaway technologies and is published by Leamington books on March 2025. You can read about it here and pre-order a copy.

Thanks for this. And, intentions matter. That’s why we discriminate between manslaughter and murder. Or accidental homicide. And, very few people are actually trained in futurism and system sciences. I was, and we were taught to excruciatingly imagine, anticipate and model out all kinds of unintended consequences and black swans. We studied them. Maybe there should be a licensing that recognizes this is a discipline.

And please add Apple Pay

Great article. Didn't know about the Sparrows Campaign.